Theories of Change

How can Architecture effectively respond to climate impacts?

Adapted from KPF Paul Katz Fellowship report “Body, Building, Block”

With climate change a pressing concern, sustainability, adaptation and resource management have become critical discussions in global urbanism. In cities across the globe, particularly arid regions, climate change impacts are already affecting daily life from dangerous and deadly record temperatures in the summer to concerns about lack of potable water and desertification. However, the severity of the problem, and the difficulty of its paradoxical nature - a global phenomenon with local impacts - stymie a coordinated and forceful response (Ayers, 2011, pg. 62). It is therefore critical to commence architectural research with a survey of theories of managing extreme change to delineate at what scales and through which methods architectural design can effectively respond to climate impacts.

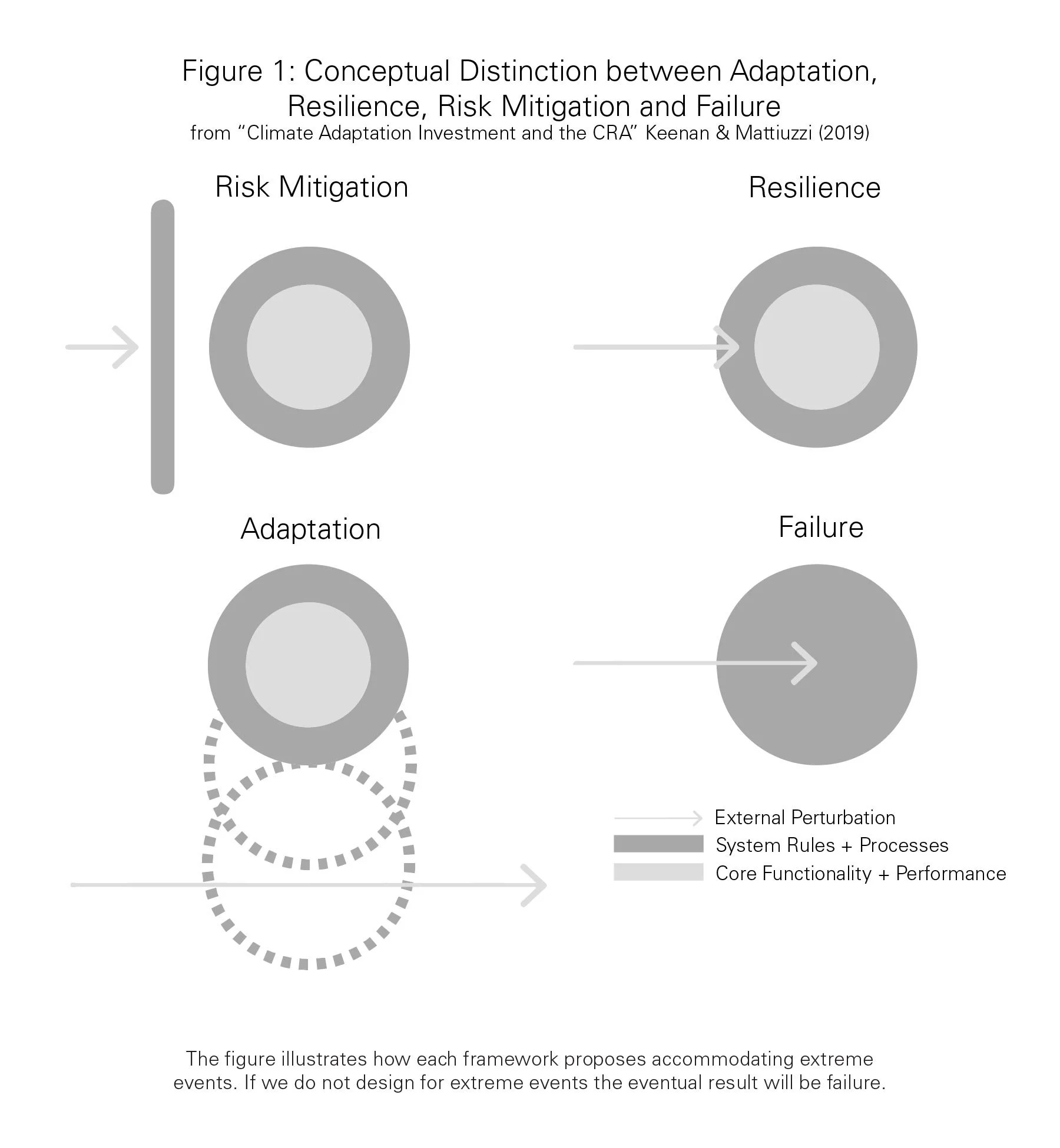

The terms mitigation, resilience and adaptation are often used interchangeably to describe attitudes and policies of response to extreme change. However, each theory is distinct in how it proposes we cope with changing conditions and prepare for the next impact. Mitigation considers actions at a global scale that will stabilize climate change impacts by focusing primarily on the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and the expansion of carbon sinks. This effort was defined by the IPCC in 2001 as “an anthropogenic intervention to reduce the sources or enhance the sinks of greenhouse gases” (IPCC, 2001). This response to change is focused on reducing anthropogenic contributions to climate change through global actors coordinating multinational efforts such as the Kyoto Protocol or a global carbon cap and trade mechanism. Mitigation is a critical response to stabilize negative environmental impacts. However, this focus on reducing emissions must be paired with the deployment of resilience or adaptation frameworks that outline procedures for coping with imminently changing conditions (Keenan and Mattiuzzi, 2019).

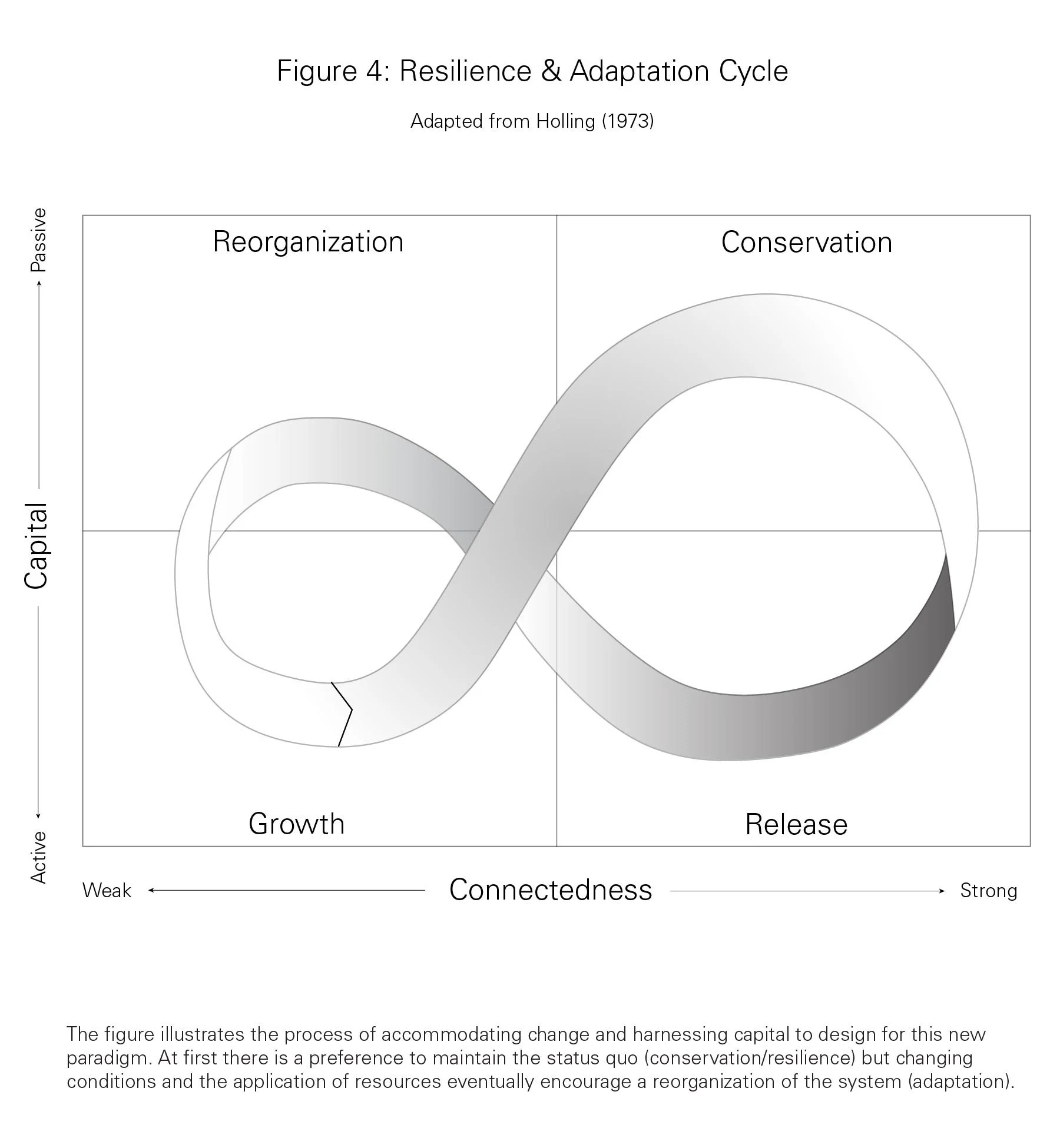

A resilience framework is concerned with withstanding the impacts of extreme change in order to ensure functionality of current systems are maintained. C S Holling proposed the seminal definition of resilience: “the amount of disturbance a system can absorb without changing states” (Holling, 1973). The United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction expanded on this definition of resilience by emphasizing an efficient return to an equilibrium state: “the ability of a system, community or society exposed to hazards to resist, absorb, accommodate to and recover from the effects of a hazard in a timely and efficient manner, including through the preservation and restoration of its essential basic structures and functions” (UNISDR, 2009, pg. 24).

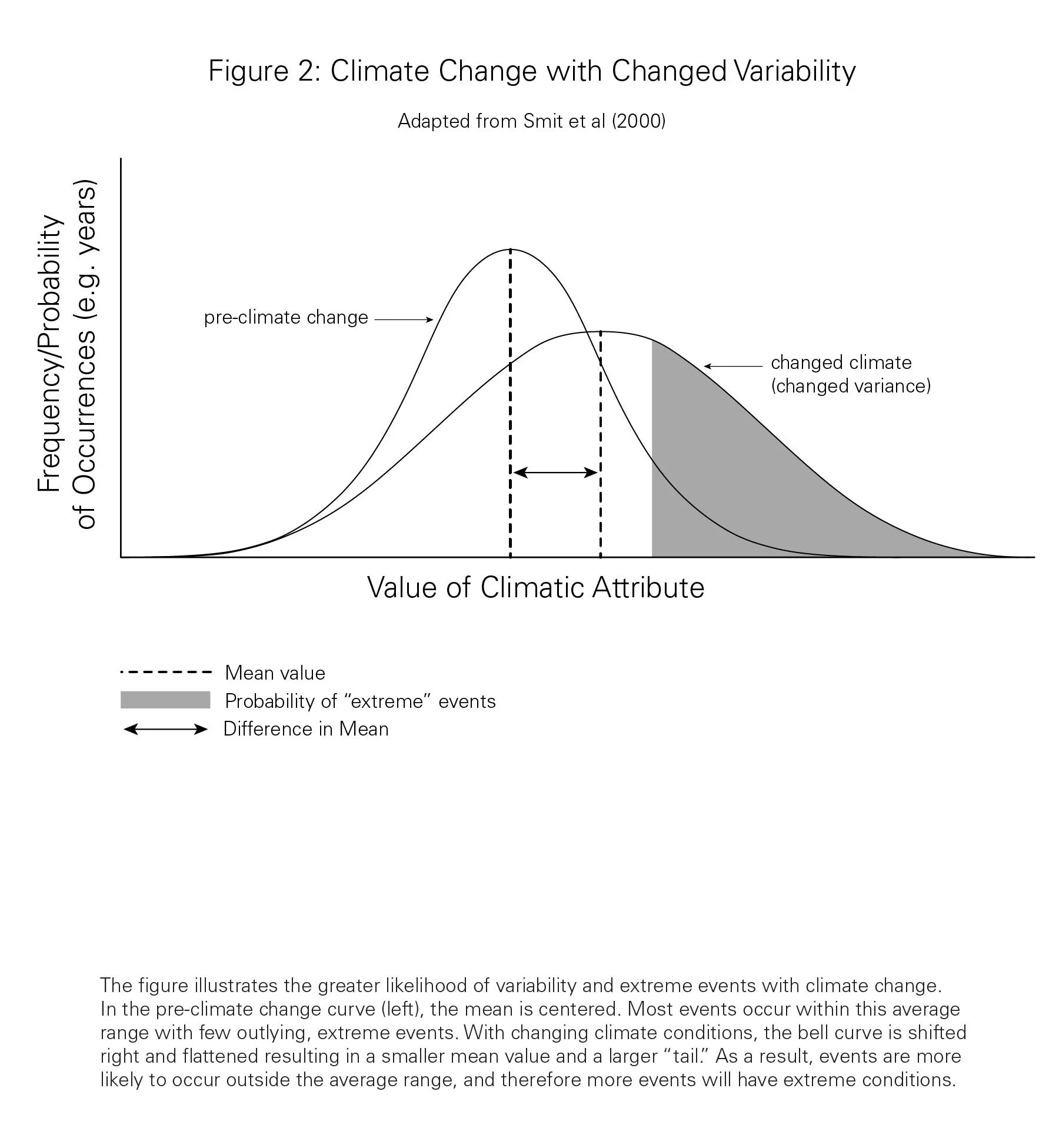

However, these and many more definitions of responding to change through a resilience framework are problematic as they assume there is a stable equilibrium state to which systems can rebound following the disturbances of climate change. In the article, “Is ‘Resilience’ Maladaptive? Towards an Accurate Lexicon for Climate Change Adaptation,” the authors argue that a resilience framework cannot applied under the conditions of anthropogenic climate as it is “not an episodic disturbance after which conditions return to a previous state; it is a combination of directional shifts in baseline conditions (e.g. increasing mean temperatures) and changes in extreme events (e.g. more frequent and intense storms and droughts)” (Fisichelli, Schuurman, and Hoffman, pg. 754).

As a consequence of the compounding conditions of climate change, one can understand that there is no possibility for maintenance of a static state or a return to prior baseline paradigm even with substantial mitigation strategies. Rather, physical and cultural adaption to accommodate the intensity and frequency of disturbances are required. The IPCC defines adaptation as an “Adjustment in natural or human systems in response to actual or expected climatic stimuli or their effects, which moderates harm or exploits beneficial opportunities” (IPCC, 2001, Ref 8, pg. 6). An adaptation framework therefore goes beyond a focus on maintenance of the status quo, and instead acknowledges that the impacts of climate change are now inevitable, and we must design systems such as buildings and cities that can accommodate change.

Adapting Architecture

The characteristics of the architectural discipline readily accommodate an adaptation framework. Architecture has always been required to accommodate changing circumstances from shifting seasonal conditions, to the alteration of building’s function over time. For instance, in his designs of scientific laboratories at the Salk Institute, Louis Kahn balanced the permeance of the architectural shell cast in concrete with the impermanence of technological spaces that would inevitably change as the equipment became obsolete (Laboy and Eannon, “Resilience Theory and Praxis: A Critical Framework for Architecture,” pg. 44-48).

Furthermore, architecture and urban design by necessity cannot be static as they are animated by people whose inhabitation and operation of the built environment are constantly in flux. Architecture is an expression of culture and therefore its use and meaning are always changing.

“It is worth considering that if architecture were limited to the scale and scope of buildings, resilience in architecture would be a purely technical or infrastructural problem “…However, architecture is not mere building, and what distinguishes architecture from buildings is its cultural value and the intentionality, often expressed through theory and evaluated through cultural criticism, to connect to the social and ecological life of the city.” (Laboy and Fannon,” pg. 41). As a result, the adaptation of the built environment is necessarily a dual project of changing both the material characteristics of the building and the social habits of users operating these spaces (Keenan qtd. in Laboy and Eannon, pg. 46).

My research titled Body, Building, Block was animated both by the physical and cultural capacity to adapt to a changing environment. Adaptation will necessitate cultural transformation as we change how live to accommodate a world that is more prone to extreme weather and storms. It will also require that we build and inhabit spaces in ways that can better mitigate extreme conditions and provide for inhabitants’ comfort. This “adaptive capacity” describes how we mobilize resources in society and the built environment to accommodate conditions outside the normal range (Smit and Wandel, “Adaptation, Adaptive Capacity and Vulnerability,” 2006, pg. 287). In an environmental context, adaptive capacity is defined as “the potential or capability of a system to adapt (to alter to better suit) climatic stimuli” (Smit et al, An Anatomy of Adaptation to Climate Change and Variability, 2000, pg. 238)

To study the adaptive capacity of a city, I looked at the culture of inhabitants and the history of buildings and the urban environment. This research sought to understand how people have mobilized resources such as capital and physical materials to adapt to the climate in the past and to project the effect of these methods in a future scenario. I observed at the scale of people and culture how lifestyle choices and cultural preferences accommodated climatic realities. From congregating after dark to establishing temporary shelter, the people of this Mediterranean city negotiated the climate through cultural expressions. These cultural choices will only become more critical as climatic conditions worsen.

In this research I also document how the design of the built environment from buildings to blocks supported this search for comfort. I was interested in the capacity of architecture designed before active systems were available, in encouraging passive comfort for inhabitants. Most buildings in the city center were designed during the Bauhaus movement. However, adjustments to this European model, allowed the structures to more successfully mitigate local climate effects such as enabling passive cooling and a reduction of direct solar heat gain. In addition, the collective nature of these adaptive designs in turn support cultural cohesion, further increasing cultural capacity to accommodate the stress of extreme change. Although the Bauhaus designs are historic models, their successful methods provide a survey of strategies that are available now to accommodate change.